- Код статьи

- S013216250017616-0-1

- DOI

- 10.31857/S013216250017616-0

- Тип публикации

- Статья

- Статус публикации

- Опубликовано

- Авторы

- Том/ Номер

- Том / Номер 12

- Страницы

- 185-194

- Аннотация

Based on the data from the"Russia Longitudinal Monitoring Survey – Higher School of Economics” (RLMS-HSE), the authors analyze the evolution of beliefs of the Russians regarding the possibility of mutual understanding and cooperation between young people and the older generation, and the factors influencing their formation. It has been shown that throughout the post-Soviet period beliefs of the Russians regarding intergenerational interaction have been positive and stable. Young people are more inclined to dialogue and cooperation between generations than older people. Such indicators of social well-being as a person's satisfaction with his/her life, feeling of happiness, propensity to trust other people, absence or weakening of loneliness increase confidence in achieving intergenerational interaction. The direct connection between intergenerational tolerance and the presence of kinship ties, as well as the closeness and degree of their intensity, which are measured by the frequency of communication and reliability of kinship assistance, has been revealed. The influence of digital technology development on intergenerational relations is limited.

- Ключевые слова

- interaction, conflict, generation, continuity, cooperation, social responsibility, social cohesion

- Дата публикации

- 24.12.2021

- Год выхода

- 2021

- Всего подписок

- 6

- Всего просмотров

- 446

Introduction. The study of problems of interaction between generations has a long history, but they began to be thoroughly studied by sociologists in the XX century. General approaches to the sociological study of these problems were developed by K. Mannheim, who emphasized the socio-cultural significance of the change of generations in the development of society, the transfer of cultural values as the main function of intergenerational relations, the problems of interaction between youth and society, the role of the younger generation as an "animating mediator" of social life [Mannheim, 1994].

Considerable attention was paid to elaboration of confrontational concepts of "generational conflict", "intergenerational relations crisis", "generational gap" etc. Particular interest in the study of confrontational issues stemmed from the rise of mass youth movements and student unrest in Western countries in the 1960s and 1970s. Researchers focused their attention on the characteristics and causes of generational conflict.

At the end of the twentieth century, the acuteness of intergenerational conflicts in Western societies decreased, and many scientists shifted the focus of their research from the concept of "conflict" to the concept of "contact" or "contract" between the generations [Kohli, 1993]. This adjusted approach focused more on the ways of reaching solidarity, cohesion of generations and revealing their specific character, rather than on proneness to conflict. But despite the predominance of one or another component in the "conflict/solidarity" ratio, young age groups were considered to be the main source of intergenerational tension [Semenova, 2002]. A new approach was also developed in the issue of generational interaction, proving that people belonging to one generation in their behavioral patterns are fundamentally different from people of another generation at the same age [Strauss, Howe, 1997].

Soviet sociologists analyzed the problems of generational interaction, as a rule, from positive standpoints of generational succession, intergenerational social movements, intergenerational mobility, family relations (A.I. Afanasyeva, V.I. Volovik, Yu. V. Eremin, I.S. Kon, B.S. Pavlov, I.V. Sukhanov, B.C. Urlanis et al.). At the same time some attempts were made to depart from concept of continuity of generations, which dominated completely at that time, and focus on study of their distinctions and peculiarities (F.R. Filippov).

In the 1990s the growth of attention to this problematic was due primarily to the development of market relations, redistribution of property, change of ideological paradigms, changes in pattern and style of life, which significantly deepened the conflict between young people and older people. Many saw the objective basis for this conflict in the instability of post-Soviet society, and the subjective - in the loss of ideological and moral guidelines or values by young people, the shortcomings of family and school education, the negative impact of the media (O.V. Gaman, V.I. Chuprov, V.T. Lisovsky, V.V. Semyonova et al.). Others spoke not just of a conflict, but of a deep generation "gap" or "split" caused by the transition of society to a different economic, socio-political system, a change in domestic and cultural standards (I.M. Ilyinsky). At the same time the research of problems of continuity of generations continued [Belyaeva, 2004; Glotov, 2004].

Further on, the study of the problems of interaction between generations in Russia continued in different directions within the framework of traditional and new approaches. But, as before, the concepts "conflict of generations" and "continuity of generations" are in the focus of attention. The problematic field of various thematic works includes the study of the root causes of modern conflict between generations [Pashinsky, 2013], various aspects (socio-professional, gender, family, etc.), the features of interaction between generations [Vdovina, 2005; Mironova, 2014; Burmykina, 2017], causes and consequences of current changes, opportunities and directions of increasing trust between generations [Semenova, 2009; Starchikova, 2012]. The topical issues of formation and development of the discourse of mutual understanding during intergenerational interaction, the achievement of solidarity between generations are being purposefully studied [Volkov, 2018]. There are attempts of sociological analysis of separate generations based on the theory of generations by N. Howe and W. Strauss [Radaev 2019; Shamis, Nikonov 2019].

The direction related to the analysis of new phenomena and processes in the field of interaction between generations, which are caused by the spread of modern digital technologies, has developed rapidly. The attention of scientists is focused primarily on the study of a new digital generation ("digital natives") opposing parents, teachers and "many confused adults" [Palfrey, Gasser, 2008], characterized by a special worldview and thinking, unusual approaches to various types of activities, leisure and entertainment, new ways of communication [Berezovskaya et al, 2015; Soldatova et al, 2017].

Despite the large number of studies on the problems of intergenerational interaction, they have not lost their relevance. In modern Russian society interactions between generations have acquired new peculiarities and features, new patterns and trends are being formed. The purpose of this paper is to analyze the evolution of beliefs of the Russians regarding the possibility of achieving mutual understanding and cooperation between different generations in the post-Soviet period, as well as the significance of certain factors influencing their formation. Particular attention is paid to the analysis of age differences. The empirical basis of the study consists of data of "Monitoring the Economic and Health Situation in Russia" by the National Research University Higher School of Economics (RLMS-HSE) "1.

Evolution of beliefs of the Russians regarding mutual understanding and cooperation between generations. The study has shown that beliefs of the Russians regarding the possibility of mutual understanding and cooperation between young people and older people are very stable. During 1994-2019 more than half of respondents assessed this possibility positively, counting on mutually beneficial cooperation and continuity of generations, whereas a little more than a third took an uncertain or compromise standpoint, and the rest denied the possibility of constructive interaction between young people and the older generation (Table 1). In different years, the greatest confidence in the feasibility of such a possibility was expressed by 15% to 24%, and complete uncertainty ranged from 3.5% to 5%. Consistent decrease of the percent of supporters of the confrontational scenario development in interrelations between generations - from 12.2% in 1994 to 7.1% in 2019 can be referred to the most noticeable long-term tendencies.

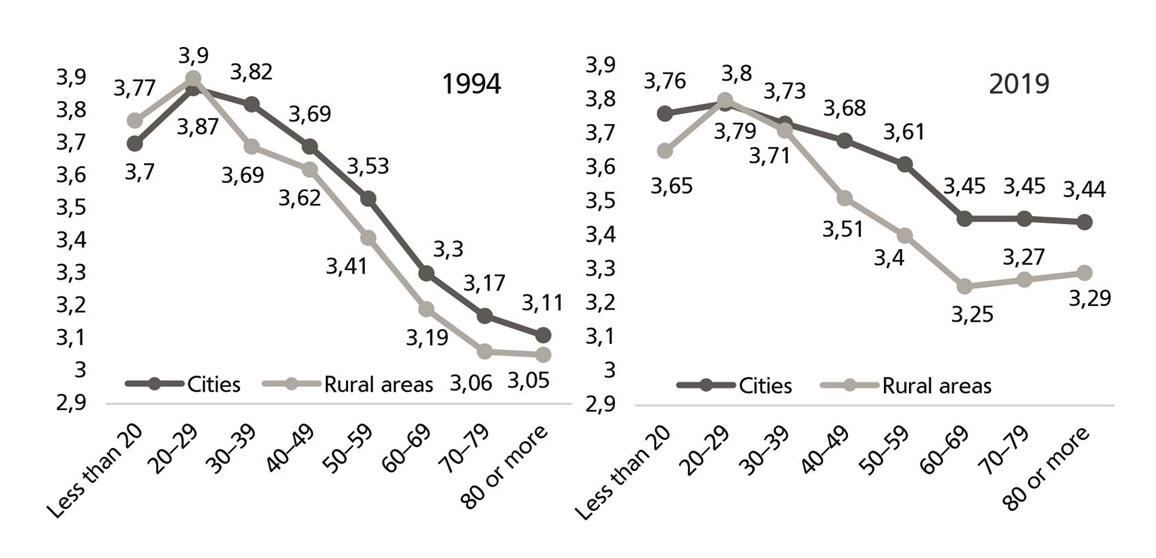

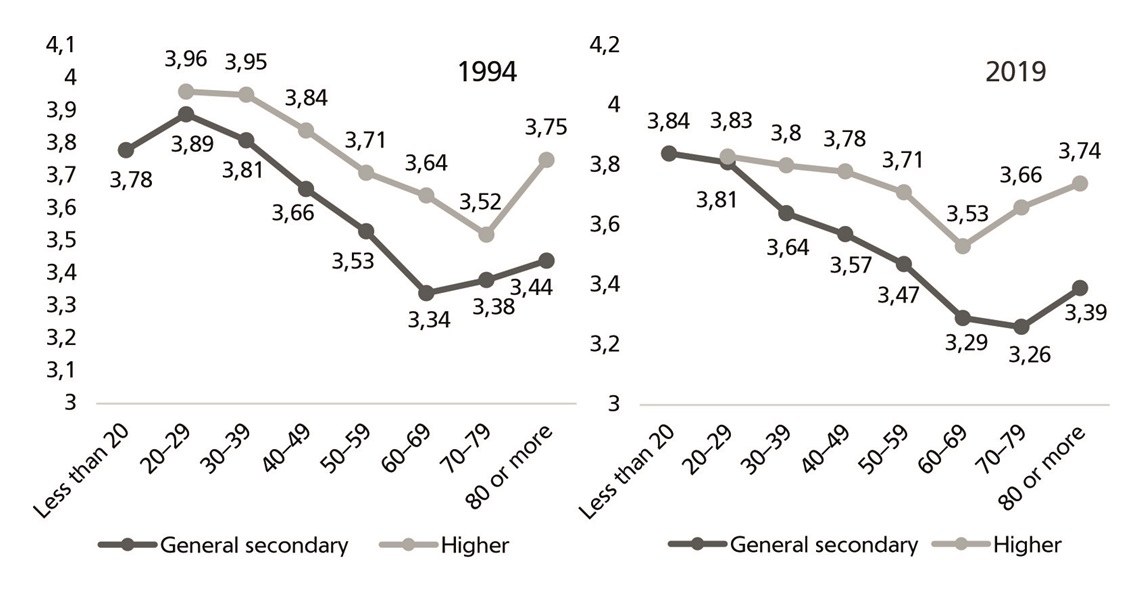

Despite the fact that the urban youth environment is characterized by a great variety of youth movements and subcultures, which are non-conformist in relation to traditional values, the conflict of generations is felt stronger in rural areas than in cities, especially in the largest cities. In 2019 among respondents living in regional centers 56.5% positively estimated the possibility of mutual understanding and cooperation between different generations, and 5.6% - negatively, whereas among the rural population there were 46.9% and 10.1% correspondingly. A similar picture was observed in all previous years. Evaluations become more optimistic as the level of education of respondents increases. The share of positive evaluations consistently increases from 45.8% among those with incomplete secondary education to 59.2% among those with higher education. The valuations of respondents with vocational secondary and higher education are more stable, the valuations of respondents with less than general secondary education are more variable.

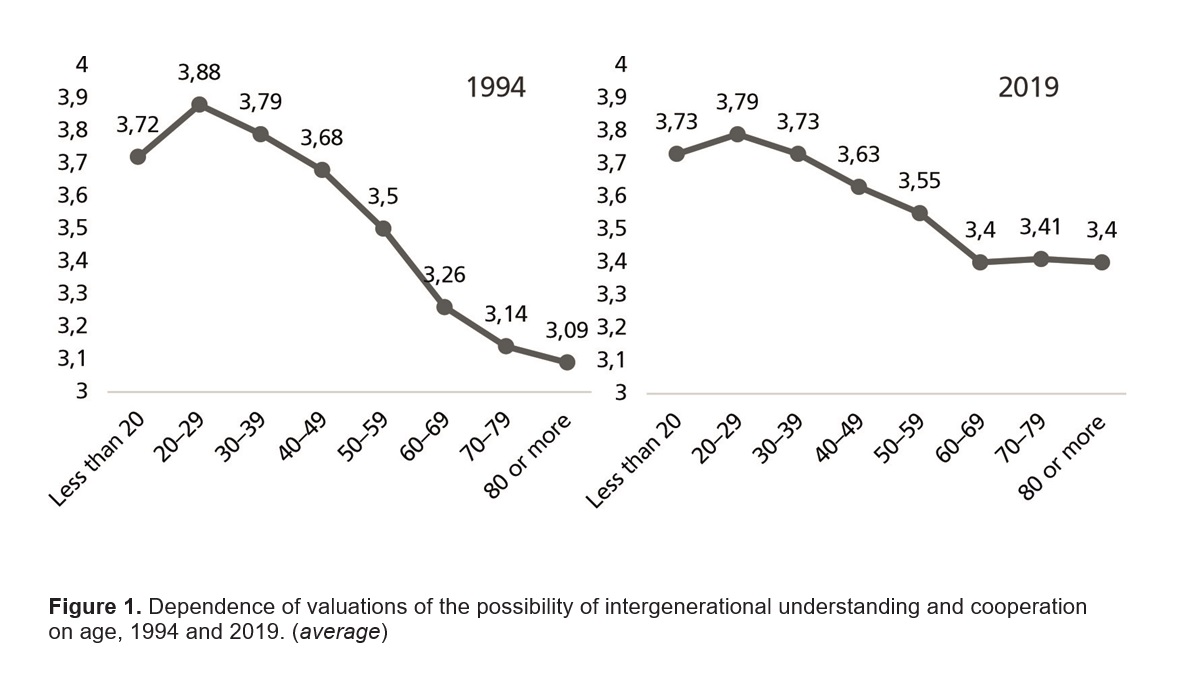

The study revealed a clear dependence of confidence in the attainability of intergenerational interaction on age, which, however, became weaker over the analyzed period (Fig. 1). Between 1994 and 2019, the difference between the maximum and minimum average valuations recorded in the 20-29-year-old and the oldest age cohorts halved. In all waves of the monitoring, the average valuation increases among Russians at age 20-29, as compared to age 14-19, but then drops sharply. Accordingly, the frequency of positive valuations decreases and the frequency of negative valuations increases as the age of the respondents raises.

Table 1

Assessing the Possibility of Mutual Understanding and Cooperation between Youth and Seniors, 1994-2019

| Year | Valuation (in %) | Mean* | Std. Dev.* | N | ||

| positive | uncertain | negative | ||||

| 1994 | 54.6 | 33.2 | 12.2 | 3.61 | 1.07 | 8893 |

| 1996 | 53.6 | 35.6 | 10.8 | 3.60 | 1.02 | 8016 |

| 1998 | 50.0 | 39.5 | 10.5 | 3.54 | 1.01 | 7890 |

| 2001 | 51.1 | 38.6 | 10.3 | 3.58 | 1.02 | 7893 |

| 2002 | 49.5 | 39.1 | 11.4 | 3.53 | 1.02 | 7877 |

| 2003 | 50.8 | 37.8 | 11.4 | 3.52 | 1.01 | 7744 |

| 2004 | 51.1 | 38.0 | 10.9 | 3.53 | 0.99 | 7714 |

| 2005 | 49.7 | 40.4 | 9.9 | 3.51 | 0.95 | 7254 |

| 2006 | 51.4 | 38.9 | 9.7 | 3.55 | 0.98 | 9320 |

| 2007 | 52.7 | 39.0 | 8.3 | 3.58 | 0.94 | 9010 |

| 2010 | 56.7 | 34.8 | 8.5 | 3.66 | 0.98 | 14300 |

| 2019 | 51.8 | 41.1 | 7.1 | 3.59 | 0.90 | 10414 |

Note. *Average and standard deviations were calculated on the basis of responses to these items using a 5-point scale: from 1 - "confident that it is impossible", to 5 - "confident that it is possible".

Figure 1. Dependence of valuations of the possibility of intergenerational understanding and cooperation on age, 1994 and 2019. (average)

The higher level of intergenerational tolerance among young Russians can to some extent be explained, as will be shown further, by the very close, trusting or good relationships they have with their parents and other older relatives, they are the prism through which the young assess the possibility of intergenerational interaction as a whole. Some rebound in 14-19-year-olds often turns out to be a consequence of peculiarities in the development of consciousness, which often arise in adolescence and youth days not from any weighty inner stimuli, but from mechanical adherence to worldview and behavioral patterns that became popular and widespread in this environment. Many of them become participants in or supporters of youth communities that exist only during adolescence. For adolescents, the rejection of dominant traditions and customs in society, rejection of the past and disbelief in authority are an expression of dissatisfaction with the "adult world" and a desire to assert loudly that they are exceptional and different from the older generation. The least tolerant with respect to intergenerational interaction are the elderly

who have the most complaints about young people and their "incomprehensible" way of life. The eternal accusations of the youth in the dissolution of morals, the rejection of traditions, disregard for the past become even louder and more persistent under the conditions of the spread of modern information technologies, which increase the distance of "misunderstanding" between the generations. At the same time, we should note that during the analyzed period the level of intergenerational tolerance among older people has increased significantly. For 1994-2019, among the elderly respondents at age 60 and older, the share of those with a positive valuation increased from 39.8% to 43%, while the share of those with a negative valuation decreased by almost 2.5 times, from 23.4% to 9.9%. A significant role in the improvement of valuations was played by the stabilization of the living standards and increased attention to the problems of the older generation as it overcame the transformation crisis, a certain adaptation of older people to the new socio-economic and public situation. These processes were accompanied by some weakening of negative elements in the consciousness of the older generation and the strengthening of conciliatory mood.

Rural young people do not differ much from urban young people in terms of age dynamics of valuations. At the same time, it is noteworthy that the confidence of youngest rural residents in the possibility of interaction between the generations has considerably decreased (Fig. 2). In old and middle age the valuations of rural residents characterized by a stronger adherence to traditions, customs and stereotypes, are much worse than those of urban residents, and this gap has increased noticeably over 1994-2019.

Figure 2. Dependence of valuations of the possibility of intergenerational understanding and cooperation on age between urban and rural residents, 1994 and 2019. (average)

At any age respondents with higher education assess the possibility of constructive interaction between generations better than respondents with lower level of education. Quite high stability of valuations among the most educated respondents, which was noticeable during the monitoring, took place in all age cohorts (Fig. 3). At the same time, the analysis of these data does not allow us to assert that young people better assess the possibility of interaction between different generations, because they are more educated than older people. In this case, both age and education are more likely to be two independent factors, with little dependence on one another.

Figure 3. Dependence of valuations of the possibility of intergenerational understanding and cooperation on age among respondents with general secondary and higher education, 1994 and 2019. (average)

The research has revealed not strong, but statistically significant connection of valuations of the possibility of intergenerational interaction with the level of material well-being of the respondents. Moreover, this connection is often stronger when not objective indicators of material well-being (income), but subjective estimates are used. One such indicator used in the RLMS-HSE is the respondent's self-assessment of a position on a 9-step scale of material well-being (from 1 - "beggars" to 9 - "rich"). In 2019, 44.1% of respondents occupying the bottom three steps on this scale were positive about the attainability of intergenerational understanding, compared with 66.7% of those occupying the top three steps (bigger by half). To a certain extent these results can be explained by the predominance of people of working age and with a high level of education among the wealthier respondents.

It is noteworthy that among wealthier respondents there are twice as many young people at age 14-29 (28.3 vs. 14.8%) as among less wealthy ones. Most of them do not represent the most successful young people, but rather the contingent that benefits from material opportunities and other achievements of their parents. In general, however, young people have a higher chance of entering the low-income strata, all other things being equal. Concern about their financial situation is widespread among young people who acutely feel the maladjustment in life and the instability of their existence, which affects their mutual relations with people of older age.

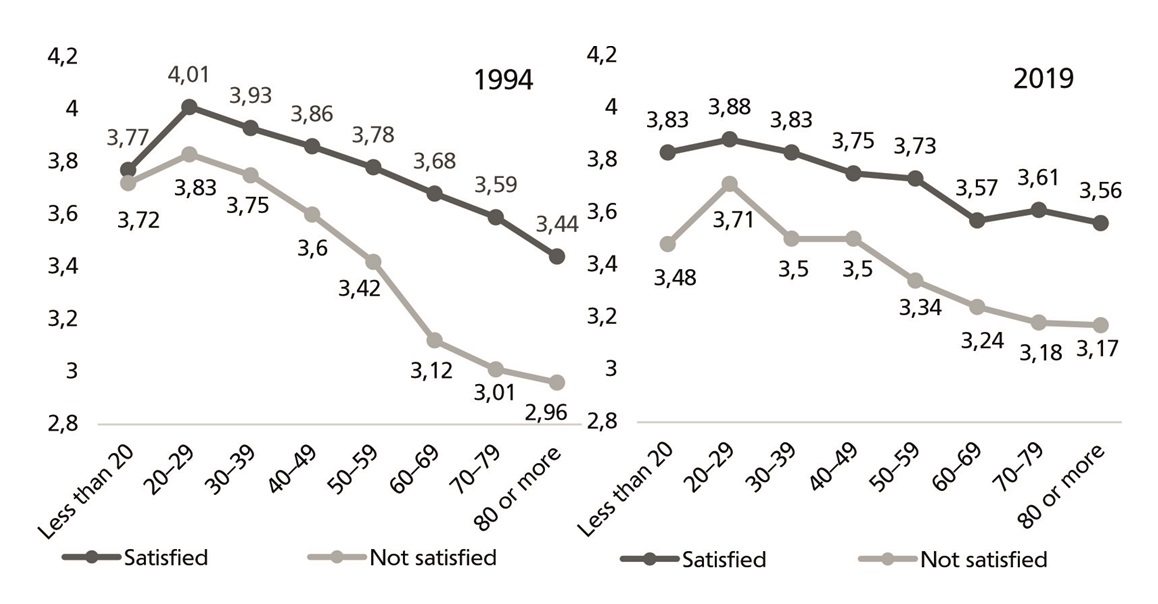

Assessment of the possibility of intergenerational interaction and social well-being. Confidence in the attainability of intergenerational interaction significantly increases respondents' satisfaction with their lives in general and feelings of happiness. For example, in 2019, among respondents who were completely satisfied with their lives, the share of people with a positive valuation was twice as high as among those who were completely dissatisfied with how their lives were going (69.2 vs. 34.9%). The depth of this difference is also underlined by the solid difference in the values of the average score - 4.01 and 3.19, respectively. The correlation between the analyzed variables increases with age. At the same time, over the period 1994-2019, the valuations of young people at age 14 - 20, who were more or less satisfied and dissatisfied with their lives, began to diverge, while those of the elderly became slightly closer (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Dependence of valuations of the possibility of intergenerational understanding and cooperation on age among respondents satisfied and dissatisfied with their lives, 1994 and 2019. (average)

The study confirmed the conclusion of our previous research that people who tend to distrust others are less likely to assess the likelihood of achieving a tolerant relationship between young people and the older generation. Equally, a tendency to trust strangers has a positive effect on people's social attitudes and strengthens the belief that such interactions are feasible. Such patterns are due in no small part to the fact that trust and tolerance are unified in their orientation. Trust, which is one of the basic foundations of social capital, implies a high level of responsibility, predictability and honesty in relationships, i.e. everything that is necessary for tolerance.

Factors that decrease the valuation of the possibility of mutual understanding and cooperation between young people and older people include the feeling of loneliness. People who feel lonely often see strangers not as a source of sympathy and help, but as a real threat to their own safety, trying to keep others at a safe distance. Therefore, respondents experiencing loneliness have less confidence in the attainability of intergenerational interaction than those who are unfamiliar with this feeling. In 2019, the average valuations were 3.32 and 3.67, respectively.

Age structure of loneliness correlates with intensity of aggravation of the problem of intergenerational interaction with age. At the same time, the increasing correlation between age and the feeling of loneliness is accompanied by a weakening of confidence in the possibility of such interaction. For the respondents feeling loneliness almost always the average valuation grows from 3,38 in the cohort of 14-19-year-olds to 4,04 in the cohort of 30-39-year-olds, but then consistently decreases to 2,97 in the cohort of 80+. Confidence in intergenerational interactions is more common among respondents with higher education, regardless of whether they experience loneliness almost always or never.

Interaction of generations: family and children. Confidence in the possibility of intergenerational interaction depends more on the nature and intensity of kin relations than on such variables as marital status, parental status and number of children. Married people assess the possibility of intergenerational interaction only slightly worse than unmarried people. At the same time, the lowest valuations were given by married people from the rural population (average valuation is 3.28 against 3.63 for urban residents). In addition, respondents who do not have children are slightly more likely to express confidence in the

feasibility of intergenerational interaction compared to those who have children. This is more true for those who are not married (3.67 vs. 3.45) than for those who have married (3.66 vs. 3.63). The influence of such factor as the total number of children has practically no effect on the valuations. But at the same time, among the respondents with children the confidence in the reality of generational interaction is lowest among those who do not have children under the age of 18 (positive valuation - 44.6%; average valuation - 3.48).

The vast majority of respondents believe they have a very close or good relationship with their parents. In 2019, 62 and 33.9% reported such relationships with their mothers, respectively, and 40.9% and 43.9% of respondents who have these parents reported such relationships with their fathers. And the more intimate the relationship with their parents, the more confident respondents were about the possibility of intergenerational interaction. Among the 14-29-year-old respondents who have very close relationships with their parents, the proportion of those who are confident in this possibility is the impressive 65%.

This data shows that people usually consider hypothetical possibility of intergenerational interaction through the lens of particular relations with their parents. But even among those who have very close relations with their parents there are many citizens who deny the possibility of such interaction. A significant part of them are people, especially young people, who hold completely different, sometimes even opposite, seemingly incompatible, views and orientations. Such people, whose consciousness is characterized by extreme inconsistency and proneness to conflict, can glowingly talk about their parents, about how caring and sensitive they are, and at the same time make completely unfounded claims to them, blaming them for their failures and misfortunes.

Kin relations play an important role in people's lives and indicate that they voluntarily agree to spend their time, psychological and other resources to maintain kinship relationships, to provide assistance in case of need. And the more often relatives belonging to different generations come into contact with each other, the closer the ties are formed between them and the better they evaluate the attainability of intergenerational interaction. It equally concerns both youth and elder generation even in cases when they have to take care of relatives in difficult situation, i.e. when they are not the main interests (Table 2). This pattern is evident in all age cohorts.

Table 2

Correlation of valuations of the possibility of mutual understanding and cooperation between generations and intergenerational mutual help, 2019*

| Frequency | How often do you take care of your children, grandchildren | How often do you take care of elderly relatives or relatives with physical or mental disabilities | ||||||

| valuation (in %) | average | valuation (in %) | average | |||||

| positive | uncertain | negative | positive | uncertain | negative | |||

| Every day | 56.6 | 37.8 | 5.6 | 3.69 | 56.9 | 36.1 | 7.0 | 3.66 |

| Several times a week | 52.2 | 42.6 | 5.2 | 3.64 | 56.5 | 37.9 | 5.6 | 3.54 |

| Once every 1-2 weeks | 49.9 | 44.5 | 5.6 | 3.53 | 61.8 | 35.0 | 3.2 | 3.52 |

| Less often | 39.6 | 52.1 | 8.3 | 3.38 | 52.3 | 43.0 | 4.7 | 3.48 |

| Never | 45.0 | 43.8 | 11.2 | 3.39 | 48.2 | 43.3 | 8.5 | 3.23 |

Note. *In this and the following table, average values are calculated on the basis of unshortened responses to items using a 5-point scale: from 1 - "confident that it is impossible," to 5 - "confident that it is possible."

The possibility of communication with parents, children, and other close relatives noticeably increases confidence in the attainability of intergenerational interaction (Table 3). This confidence grows as the frequency of communication increases, irrespective of how relatives communicate: in person or by such technical means as telephone and the Internet (Skype, social networks, etc.). Similar trends were also observed in the analysis of the relationship between valuations of the possibility of intergenerational interaction and the frequency of communication between respondents and friends and acquaintances.

Table 3

Correlation of valuations of the possibility of intergenerational understanding and cooperation and intergenerational communication, 2019

| Frequency | How often do you communicate in person when meeting your parents, children, other relatives | How often do you communicate by phone or the Internet with parents, children, other relatives | ||||||

| valuation (%) | average | valuation (%) | average | |||||

| positive | uncertain | negative | positive | uncertain | negative | |||

| Every day | 54.8 | 39.1 | 6.1 | 3.65 | 54.7 | 39.5 | 5.8 | 3.66 |

| Several times a week | 52.1 | 40.9 | 7.0 | 3.58 | 49.9 | 41.8 | 7.5 | 3.54 |

| Once every 1-2 weeks | 47.4 | 43.8 | 8.8 | 3.49 | 50.7 | 41.8 | 7.5 | 3.51 |

| Less often | 44.1 | 46.7 | 9.2 | 3.45 | 46.7 | 42.8 | 10.5 | 3.48 |

| Never | 31.8 | 55.3 | 12.9 | 3.23 | 36.1 | 48.1 | 15.8 | 3.22 |

A significant role in the formation and development of the current conflict of generations in Russia is played by different content of the modern demand of generations for changes in socio-economic and political fields, as well as the deepening gap between them in mastering modern information technology, which has increased the confrontation of values and principles to live by of the older and younger generations. Values and principles to live by of the older generation are losing their meaning and practical significance, and are not inherited by the young. Many young people today live in a special world of their own, which distances them from the world of the older generations. And today's young people live not just in another world, but in a fundamentally new digital world. They have different interests, different communication, different practices, different ethics. Apparently, the technological gap between generations has never been as tangible as it is today [Berezovskaya et al., 2015; Soldatova et al., 2017].

Furthermore, according to RLMS-HSE data, young people identify themselves with their generation much more often than older people. In 2018, among 14-19 year old respondents, 72.6% often felt an affinity, a unity with people of their generation and 22.8% - rarely. As we moved to each older cohort, these rates worsened, reaching a minimum level in the 80+ cohort (49 and 37.3%, respectively).

Despite these differences, however, from the perspective of young people, as shown above, the generational gap does not look as deep as it does from the perspective of older people. Young people have different consumer habits compared to adults, they use the achievements of modern information technology more often. But the fact that young people always feel an acute need for special, their unique ways and forms of communication, a peculiar information world, different from the world of adults, does not mean that they reject traditional ways and forms of communication. The impact on intergenerational relations of the rapid development of digital technology, which is primarily invading the daily lives of young people, is so far limited. RLMS-HSE data analysis did not reveal any serious correlations between young people's valuations of the attainability of intergenerational interaction and indicators of Internet technology use. Compared to their equals in age, only 14-20-year-olds who spend too much time using electronic devices or are overly engrossed in video or computer games show a slight deterioration of their valuations. The number of young people who can be referred to as digital generation is still small. They constitute a narrow segment of the most advanced urban youth armed with innovative computer technology and modern gadgets, quickly learning and easily mastering new information technologies.

Conclusion. Beliefs of the Russians regarding the attainability of intergenerational interaction is characterized by the prevalence of a positive spectrum and high stability. Throughout the period under analysis, the share of respondents who were confident in the possibility of mutual understanding and cooperation between young people and older people was several times greater than the share of those who denied this possibility. Urban residents, more educated and financially secured citizens are more optimistic about the attainability of intergenerational cooperation. Young people are more inclined to dialogue and interested cooperation between generations than older people. But in recent years the level of intergenerational tolerance among older generation has increased. Such indicators of social well-being as life satisfaction, feeling of happiness, tendency to trust other people, absence or weakening of feeling of loneliness considerably increase confidence in attainability of intergenerational interaction. Importance of these factors increases with age. Confidence in the possibility of intergenerational interaction has little dependence on such formal indicators as marital status and number of children. But at the same time a direct connection between intergenerational tolerance and the presence of kin relations, as well as the closeness and degree of their intensity, which are measured by the frequency of communication (personal and using technical means), the reliability of kinship assistance, has been revealed. The generational gap manifests itself more at the level of practices, but not values. The impact of digital technology on intergenerational relationships is limited and fragmented. Along with forward-minded "digital" youth, there are large groups of young people in society who differ little from other citizens in many key respects.

Библиография

- 1. Belyaeva L.A. (2004) Social Portrait of Age Cohorts in post¬Soviet Russia. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya [Sociological Studies]. No. 10: 31–41. (In Russ.)

- 2. Berezovskaya I.P., Gashkova E.M., Serkova V.A. (2015) “Digital” Generation: Prospects Phenomenological Descriptions. Rossija v globalnom mire [Russia in the Global World]. No. 7(30): 53–64. (In Russ.)

- 3. Burmykina O.N. (2017) Intergenerational Family Contract: The Views of Younger Generation.

- 4. Peterburgskaya sotsiologiya segodnya [St. Petersburg Sociology Today]. Iss. 8: 150–159. (In Russ.) Glotov M.B. (2004) Generation as a Category of Sociology. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya [Sociological Studies]. No. 10: 42–49. (In Russ.)

- 5. Kohli M. (1993) Public Solidarity between Generations: Historical and Comparative Elements. Research report 39. Research Group on Aging and the Life Course. Free University of Berlin. Berlin: Institute of Sociology

- 6. Manheim K. (1994) The Diagnosis of Our Time. Moscow: Yurist. (In Russ.)

- 7. Mironova A.A. (2014) Intergenerational Solidarity of Relatives in Russia. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya[Sociological Studies]. No. 10: 136–142. (In Russ.)

- 8. Palfrey J., Gasser U. (2008) Born Digital: Understanding the First Generation of Digital Natives. New York: Basic Books.

- 9. Pashinsky V.M. (2013) Sociology of Knowledge оn the Generations Formation Mechanism. Sotsiologicheskiy zhurnal [Sociological Journal]. No. 1: 47–63. DOI: 10.19181/socjour.2013.1.363. (In Russ.)

- 10. Radaev V.V. (2019) Millennials: How Russian Society is Changing. Moscow: VShE. (In Russ.)

- 11. Semenova V.V. (2002) Social Portrait of Generations. In: Drobizheva L.M. (ed.) Russia is Reforming. Moscow: Academia: 184–212. (In Russ.)

- 12. Semenova V.V. (2009) Social Dynamics of Generations: Problem and Reality. Moscow: ROSSPEN. (In Russ.) Shamis E., Nikonov E. (2019) Theory of Generations: Extraordinary X. Moscow: Synergiya. (In Russ.)

- 13. Soldatova G.U., Rasskazova E.I., Nestik T.A. (2017) The Digital Generation of Russia – Competence and Safety. Moscow: Smysl. (In Russ.)

- 14. Starchikova M.V. (2012) Intergenerational Interaction in Modern Russia. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya [Sociological Studies]. No. 5: 140–144. (In Russ.)

- 15. Strauss W., Howe N. (1997) The Fourth Turning: An American Prophecy. New York: Broadway Books.

- 16. Vdovina M.V. (2005) Inter¬generation Conflicts in Contemporary Russian Family. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya [Sociological Studies]. No. 1: 102–104. (In Russ.)

- 17. Volkov Yu.G. (2018) Intergenerational Interaction in Russian Society: The Search for a Language of Consent and Mutual Understanding. Gumanitariy Yuga Rossii [Humanities of the South of Russia]. Vol. 7. No. 3: 30–42. DOI: 10.23683/2227¬8656.2018.3.2. (In Russ.)